-

Derrik Westoby of PBS Engineering and Environmental uses drones for mapping and surveying. Provided photo

-

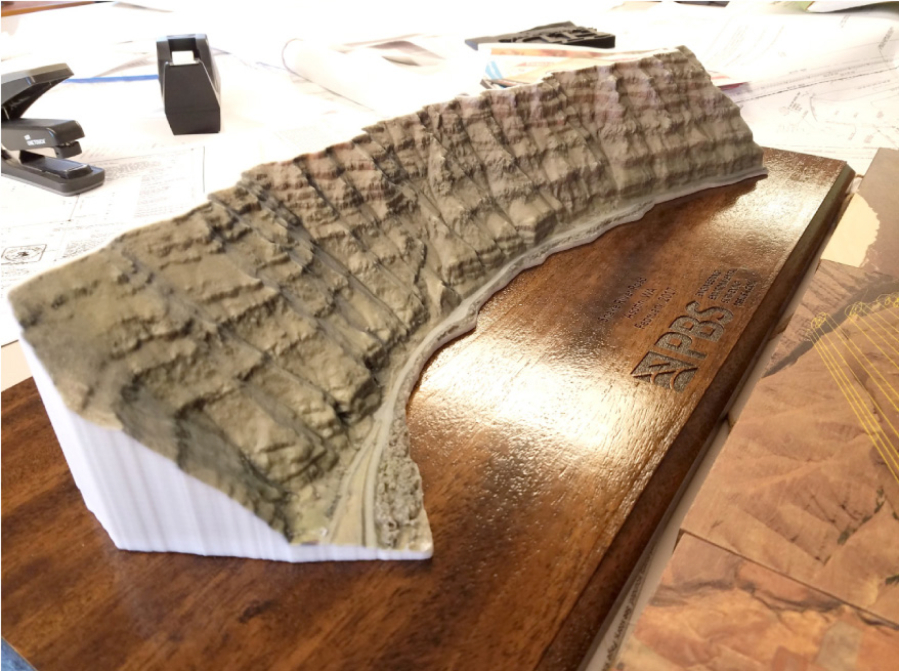

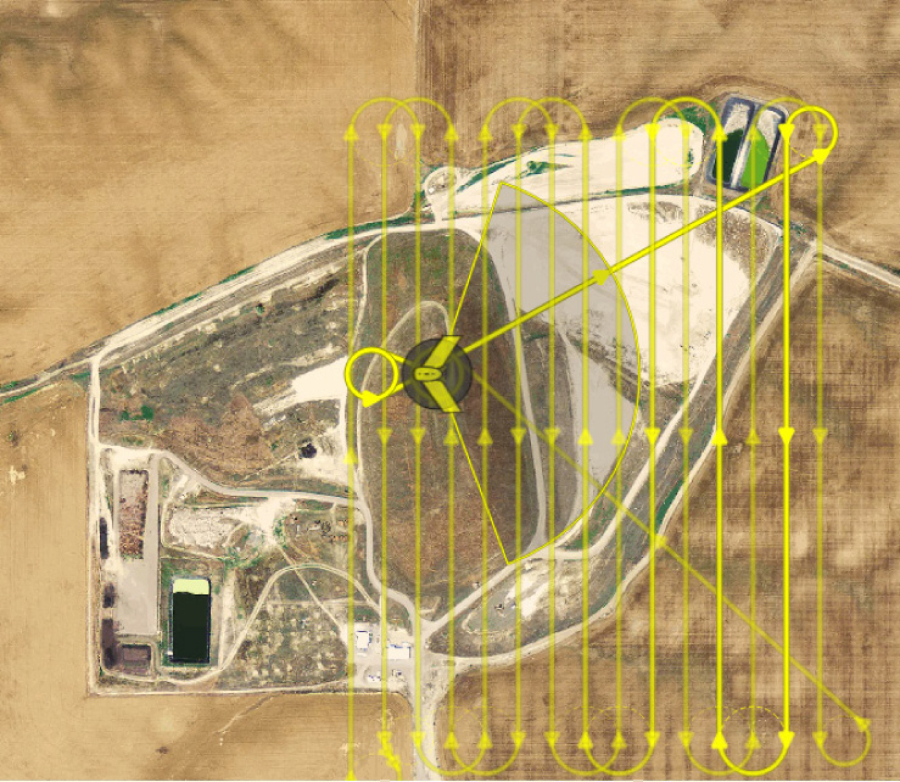

The data Derrik Westoby’s aircraft collect via preprogrammed flight patterns can be used in creating detailed 3-D representations of the Earth’s surface. Provided photo

-

PBS Engineering and Environmental uses drones to capture images for mapping and surveying. Provided photo

-

Provided photo

-

Marketing entrepreneur Jeremy Gonzalez, right, uses drones to take his commercial photography and videography to new levels. Provided photo

A A

No one you’re going to read about here is a spy.

That detail must be cleared up first, because it’s typically the first question they are asked.

Derrik Westoby considers it an opportunity to educate when people see him flying his drone.

“What is that?”

“You doing surveillance?”

“Who are you spying on?”

The more he can share about what he can do with the technology — by the way, peeking into windows is by far one of the hardest tasks, and one that someone who went through the trouble of getting a license is not likely to risk it for — the better liaison he can be for the Unmanned Aircraft Systems flying community.

“Chances are, everybody I come across with my drone is seeing it for the first time,” Westoby said. “It’s spreading the message that there are people being responsible with them.”

The use for the technology has integrated mightily since Westoby began learning how to navigate and build the machines on his own four or so years ago.

He’s a testament to that. Seven months ago, PBS Engineering and Environmental, an engineering and environmental firm with offices all over the Northwest, including Vancouver, contracted with him to capture data from his aerial camera for use in mapping and data collection. He has since been brought him on as a full-time employee and an entire department has been created around the work.

It was a bold move, PBS being one of the first design companies in the nation to have an Unmanned Aerial Services Division.

It was also a huge stretch from where Westoby started. After service in the military, the Bend, Ore., native worked as an EMT for Milton-Freewater Rural Fire and took up an interest in drone technology. He spent $40 on his first consumer-grade product.

He imagined how the technology could be used to help on the front lines with major forest fires, which is not practical yet.

In the meantime, he learned to fly in the open fields of the rural community and built his own aircraft.

Westoby now serves as the Walla Walla-based program lead for the division in PBS’ 10 regional offices, training other pilots for the company. Pilots like him, he said, “got over the hump where people acknowledge there is an application. There is a use in a lot of professions for the technology.”

New perspectives

From local companies to the U.S. military, to Lady Gaga and Amazon, more businesses are interested in the capabilities and value of the high-flying devices.

Jeremy Gonzalez, a marketing entrepreneur whose Spark Creative uses drone photography and videography for content creation, was touting the technology before anyone would actually listen.

So he showed them instead.

Gonzalez, who considers himself “TransCascadian” because of his work in Eastern and Western Washington, mastered flying in Seattle’s Gas Works Park. With footage from his DJI drone, he launched the Facebook page “ABOVE Seattle,” showcasing the dreamy skyline of the bustling city.

The videos are all his creation. With more than 13,000 page followers, one of his videos has garnered around 190,000 views and more than 3,000 shares.

“When that happens, people start emailing me,” he said. “Hey, do you work with businesses?”

The drone portion of his business accounts for only about 10 percent of his income.

“Five or six years ago, to get the quality of shots I have now I would have had to hire a helicopter,” he said.

His video work has garnered attention not only from clients, but also from national media firms in need of footage. He’s sold footage to CNN and CBS for a “48 Hours.”

“When I started ABOVE Seattle, if I would have gone to a company for sponsorship and asked for $1,000 a month to do it, no one would have given it to me,” he said. “Now they can see what I built from scratch, and they contact me.”

The work has changed the way he views the world around him.

“I shot videos and a little photography for a long time, but until I started flying I’d never framed the world like I frame it now,” he said.

Coldwell Banker First Realtors Marketing Coordinator Stephanie DeLay is working toward her pilot’s license for Unmanned Aircraft Systems.

The office has invested in its own DJI drone. The vision is to use it to showcase high-end and large-acreage properties to potential buyers.

“We’re trying to capture the whole setting. Properties that have a few acres, so we can show the buyers how they’re arranged,” DeLay said.

“Buyers are wanting more and more information. You can offer photos, 3-D tours. It’s an information-hungry group.”

The drone technology was demonstrated last year in waves of green wheat in Dayton, and is being used in precision agriculture and viticulture at Walla Walla Community College.

But while drone technology moves forward, in other circles it remains as challenging as ever to use.

Potential turbulence

Westoby, one of the most well-versed pilots in terms of understanding permitting, air space regulations and compliance, has on numerous occasions been told he can’t use air space above private or even public property, even though the FAA is the only regulatory body governing air.

Just last week Westoby shot overview footage of the Walla Walla Regional Airport. Although he had an active FAA airspace waiver for the area, it took nearly four months to get approval to fly there. He said he coordinated with air traffic control before, during and after the flight. Some traffic was rerouted during his flight. But the footage was incredible.

And, of course, the technology itself is tricky.

“There’s a lot of ways for stuff to go wrong,” Westoby said.

A speck of dust in an airspeed sensor can throw off the machine; if it’s supposed to be moving at 30 mph, it may go 15. Depending on the settings, it can correct itself by shutting off or have an array of other responses.

At PBS, the drones are used to create survey-controlled orthomosaics (geo-referenced aerial maps for planimetrics — measuring a surface by tracing its boundaries), supplementing traditional topographic survey methods.

With software by Skyward, flight paths are planned in advance. The data collected can be used to generate 3-D surface meshes, contour lines and 3-D models — without making another field visit.

Other applications include virtual inspections, site visits and visual assessments of hard-to-access areas. Benefits include risk reduction to field staff and increased efficiency.

PBS expects to extend the applications to more commercial and public clients to support engineering, environmental and survey services, it said.

“We’re excited to offer this technology to clients in all sectors — not just municipal surveys,” PBS Principal Engineer Mark Leece said in a prepared statement. “The sky is literally the limit.”

Want more local business news?

Sign up for our Business Newsletter.

No comment yet, add your voice below!